Sweet Sixteen

Thanks to NirvashTec for helping me source vital material and documents that helped with the build.

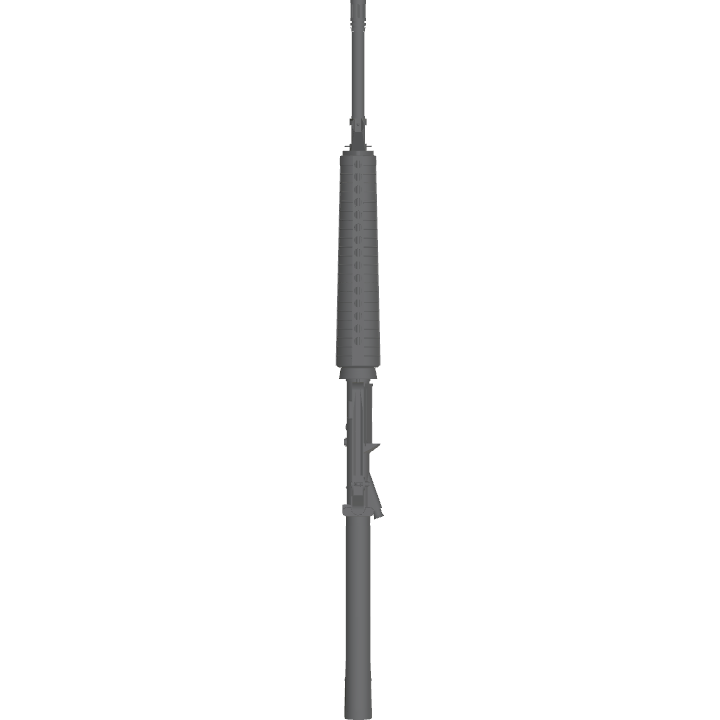

Summary

The M16 Rifle, formally Rifle, caliber 5.56mm, M16, is an American assault rifle designed by Eugene Stoner, Jim Sullivan, and Bob Fremont at Armalite, and manufactured by Colt's Manufacturing Company, among others. A direct descendant of Stoner's earlier work with the AR-10, it was Jim Sullivan and Bob Fremont who scaled the AR-10 down to the AR-15.

A weapon controversial for its technical qualities, ballistic performance, and initial procurement decisions, it soon matured into an accurate, powerful, and reliable weapon. The extensive use of computer-controlled machining, aircraft-grade aluminum, and the use of a small-caliber, high velocity cartridge was nothing short of revolutionary.

The longevity of the M16 can be attributed to its simple and sophisticated design which gives it legendary accuracy, lethality, and adaptability while keeping it reliable, rugged, easy to use, and easy to maintain.

History

Formally adopted by the US Air Force in 1964, it and its derivatives have remained the standard service rifle of the US military. 8 million M16s have been made, with 90% still in use.

Not bad for a rifle over 50 years old.

Background: Armalite and the AR-10

Many technical aspects of the AR-15 can be traced back to the AR-10. While designed for the larger 7.62mm NATO cartridge, the AR-10 would share many features of the AR-15 such as the Stoner expanding gas system, in-line stock and buffer tube, multiple radial rotating locking lugs, the extensive use of aircraft-grade 7075-T6 aluminum alloys, and the use of computerized numerically-controlled machining.

These were technologies almost unthinkable 20 years earlier; the specific alloy employed was first developed secretly in 1935 by Sumimoto Heavy Industries, introduced by Alcoa Industries in 1943, and standardized in 1945. It’s first major use was with the famous Mitsubishi A6M Zero carrier fighter, renowned for its speed, range, and agility in part due to the alloy.

Numerically-controlled machine tools were an even more recent invention, with a decade of work by John Parsons and Frank Stulen just bearing fruit as these systems entered the production line. They were such a shift that the US Army purchased 120 and leased them to aircraft companies just so they’d use them. Throughout the development of the AR-10 and AR-15, such machines were being rapidly improved upon for their value in the aircraft industry.

The use of aircraft-grade aluminum and CNC milling is a result of Armalite’s nature; it was a subsidiary of Fairchild Aircraft, primarily focused on research and development specifically regarding the use of established aerospace practices in manufacturing and materials in firearms. As such, there were other designs by Armalite which made it to the mass market, to include the AR-7 survival rifle and the AR-18 assault rifle.

This also meant that while they did have some production capacity in their facility in Hollywood, California, many of their designs would be manufactured by other companies under license or by selling the rights; the AR-10 would be made under license by Artillerie-Inrichtingen in the Netherlands, the AR-15 would have its rights sold to Colt, and the AR-18 would be manufactured by Howa in Japan, and by Sterling in the UK. It should be noted that the current Armalite, founded by Mark Westrom in 1996, is a completely new company which purchased the name and some design rights of the original Armalite.

While the AR-10 was a success, it was not exactly the success hoped for, with its production divided over many small contracts and failing to be adopted in major trials in the US, Finland, and West Germany. The largest contract was to Portugal, who intended to make it their standard rifle but ran into political issues due to the controversy surrounding the then-ongoing Portuguese Colonial War. Another contract was for Sudan, who purchased a number which would see very hard use during the long and bloody Sudanese Civil War.

In the AR-10, Armalite had a modern rifle made with the latest developments of the aircraft industry, but squandered on a cartridge that while technically just as new, was rooted in an era when horse cavalry, volley fire on command, and the bayonet were considered important tactical elements.

All it needed was a cutting-edge concept to go with it, and modern operations research, a recent development only two decades old at the time, would provide it.

Hickman and Hall’s Papers: Study for Success

After WWII, the US Army Ordnance Department conducted research to evaluate American performance in the field, to include the effectiveness of their small arms. In 1952, two very influential studies were concluded; Operational Requirements for an Infantry Hand Weapon by Norman Hickman under the Operations Research Office, and An Effectiveness Study of an Infantry Rifle by Donald Hall under US Army Ordnance’s Ballistics Research Laboratory.

Hickman’s study concluded, among other things, that rifles tend to be used no further than 300 yards since that’s about as far as most people can see people, and that the accuracy of the average infantryman drops dramatically past 100 yards. It recommended a "salvo-type automatic" weapon which fired several projectiles at once to improve hit probability between 100-300 yards. It was also suggested that a smaller-caliber automatic weapon in the region of .20 caliber fired in short bursts could achieve a similar effect due to the lower recoil.

Hall’s study was mainly focused on the ballistic effectiveness of ammunition, and concluded that a rifle firing a smaller-caliber, higher-velocity cartridge is superior than the then-standard .30 caliber rifles in regards to single-shot performance, the combined weight of the rifle and ammunition, the reduced weight for the same amount of ammunition carried, and on the basis of inflicted casualties per a given weight.

Hickman and Hall’s studies would influence the decision to develop and eventually adopt the AR-15, as it paved the way for its future adoption as the M16.

Trials: Testing the Waters

In 1957, the US Army accepted a request by Gen. Wyman of the US Army Continental Command for a .223 caliber select fire rifle, which weighed 6 pounds with a loaded 20-round magazine. Said rifle also must have comparable or greater wounding power than the in-service M1 Carbine, and must pierce a US M1 Helmet at 500 yards.

As a result of this request, a variety of light rifles were submitted in 1958. Armalite submitted ten AR-15 rifles with one hundred 25-round magazines to the trials. The results were positive; a 5-7 man team with AR-15s had more firepower than 11 men with M14s, that soldiers armed with AR-15s could carry on average three times the ammunition, and that the AR-15 was three times more reliable than the M14. However, then-Army Chief of Staff Gen. Maxwell Taylor vetoed the AR-15 in favor of the M14. This lack of results, as well as financial difficulties, led Armalite to sell the rights to the AR-15 to Colt.

Colt redesigned the rifle to make it more suitable for mass-production, and moved the charging handle to the rear of the upper receiver, where it is today. They then conducted a Far East tour, which was quite successful and resulted in a 1959 sale to Malaya.

In 1960, Colt representatives at an outdoor party demonstrated the rifle to US Air Force General and Vice Chief of Staff Curtiss LeMay. LeMay was suitably impressed, and ordered 8,500 AR-15s for use by the USAF.

Despite objections by Gen. Maxwell, further trials were conducted with the AR-15. The US Army found that on average, soldiers with the AR-15 scored better in marksmanship tests than counterparts with the M14, and the lighter recoil made it more suitable for automatic fire. Under the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA, the AR-15’s trials in Vietnam by US Special Forces and ARVN forces were decidedly positive, praising the rifle’s reliability and stopping power, and pressed for its immediate adoption.

However, the Army became more entrenched in its view toward the M14, and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had conflicting information between the Army and the Air Force and ARPA. McNamara ordered Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance to evaluate the effectiveness of the AR-15, the AK-47, and the M14. The Army concluded the M14 was the best, but Vance ordered the Army Inspector General to investigate the tests. It was discovered that all the testers had a strong bias toward the M14.

A Hasty Adoption: Calm before the Storm

In early 1963, McNamara discovered that M14 production was insufficient to meet current demand and ordered its production halted. This left a substantial gap between the M14 and US Army Ordnance’s planned replacement; the Special Purpose Infantry Weapon, or SPIW.

SPIW was based on the Hickman report's recommendations, developing weapons that fired very light and high velocity darts at an extremely high rate of fire in a mechanically-set burst. They also stuck a semi-auto 3-shot 40mm grenade launcher for good measure. However, such a complex weapon needed more time to be ready.

As a result, something was needed to fill the gap between the end of M14 production and the beginning of SPIW, and in November of 1963, McNamara ordered the universal adoption of the AR-15 as the M16, with an order of 85,000 rifles. This was over the Army’s objections over the lack of a chrome-plated chamber, although a concession was made for the forward assist. Air Force rifles would be known as the M16, where the Army model was the M16A1. The primary difference is the latter has a forward assist.

In March 1964, the Army received its first batch of M16A1 rifles, and by 1965, they would be in use in Vietnam.

Entry into Service: Baptism by Fire

The initial fielding of the M16A1 was nothing short of a disaster. Rifles jammed, and soldiers and marines died. Congress got word, and with the Vietnam War in full swing, they launched a thorough investigation.

The result was that a combination of factors which on their own would be bad, but combined into a disaster. Poor training since they were issued in theater without prior familiarization, the lack of any cleaning kits, untested changes to propellants and its effect on weapon cycling, and corroded bores and chambers all resulted in a slew of problems.

The powders in particular are contentious, with the designer Jim Sullivan firmly believing that changing the type of gunpowder used in the ammunition was an attempt to sabotage the weapon, where others point to the production difficulties of the desired powder and thus a shift to the other type without proper testing to ensure it worked.

Whether it was negligence or sabotage by who in the whole process was never identified. But the problems were, and solutions came quick and fast; cleaning kits with a comic-style field manual on weapon maintenance ensured soldiers could take care of their weapons, and the M16A1 was updated with improvements such as chrome-lined chambers and a new buffer that allowed the rifle to work with the new powders. The powders were altered again to produce less fouling.

As a result, reliability dramatically improved and successfully restored faith in the weapon by the soldiers and marines who carried it. By early 1967, the M16 series became far more widespread, and to popular acclaim. In 1969, the M16 would become the standard-issue rifle of the US Armed Forces. The success of the M16 would influence design work elsewhere, including the USSR.

Upgrades: Enhancing Excellence

The M16 assault rifle would see iterative development over its lifespan, both to accommodate for the desires of various services as well as to exploit new developments in optics mounting.

M16: Air Force Original

The original M16 would be used by the USAF Security Forces. It can be distinguished by the lack of a forward assist, which the Air Force alongside Eugene Stoner did not believe was necessary. The lower receivers also lacked a protective shield around the magazine catch. Combined, these features are known to collectors and enthusiasts as “slab-sided” receivers. Apparently, the US Air Force did not run into many of the same issues as the Army rifles, and these rifles would continue to be employed into the 21st century, with gradual updates.

M16A1: Army Classic

The model which the US Army and Marine Corps carried in Vietnam. These weapons have a forward assist, as well as raised areas around the magazine release button to prevent accidentally dropping the rifle’s magazine.

The M16A1 would use both the “duckbill” 3-prong flash hider and the “birdcage” flash hider. This change is not unique between the M16 and M16A1, as both weapons would be seen with them.

Later on, the distinctive triangular handguards were replaced by the round handguards. While the triangular model was considered to be a fairly comfortable and effective design, it required distinct left and right halves. The round handguards, derived from those used on the CAR-15 carbines, would have two interchangeable top and bottom halves.

Many M16A1 were given new barrels upon the adoption of the M855 cartridge, as they required the bullet be spun more quickly at a rate of 1 turn in 7 inches to properly stabilize the heavier 62-grain (4.0g) semi-AP bullet, versus the 1 turn in 12 inches necessary for the older and lighter 55-grain (3.5 g) bullets of the M193 round.

This model proved the capability of the M16 and its concepts, and would see extensive service not only in the US but around the world. While the rifle is no longer employed by the US Armed Forces, the M16A1 remains in widespread service around the world in active and reserve forces, including Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Israel, Singapore, and South Korea. The M16A1 would be manufactured under license in the Philippines, Singapore, and South Korea. In addition, an unlicensed clone known as the Norinco CQ is manufactured in the People’s Republic of China.

M16A2: Marine Corps’ Changes

In the 1980’s, the M16 series would be updated as a result of input from the US Marine Corps. The list of changes included a thicker barrel profile past the handguards, brass deflector, a revised rear sight unit for greater adjustability with options from 300-800 meters, a tritium-illuminated front sight, a stronger and longer buttstock, a pistol grip with a “finger rest,” a revised “birdcage flash hider” which doubled as a compensator, a strengthened lower receiver, and a 3-round burst limiter.

The US Army was largely satisfied with the M16A1, and it would be the Marines who would receive the new M16A2, receiving their weapons in 1983, followed by Army adoption in 1987.

The US Navy would adopt the M16A3, which had all the various changes except that the weapon was capable of fully automatic fire.

M16A3: Navy's Say

The M16A3 is a variant of the M16A2. The sole difference between the two is that the M16A3 is capable of fully automatic fire. Otherwise, the weapons are identical. They are primarily utilized by the US Navy as well as for export.

M16A4: Future on Rails

In 1994, the US Army’s Picatinny Arsenal would develop a new rail system. Formally the MIL-STD-1913 rail, it is more popularly known as the Picatinny rail. This would be incorporated into the M16 series as the M16A4, replacing the “carry handle” with a Picatinny rail, although they often came with a detachable rear sight that mimics the carry handle.

With the adoption of a railed handguard designed by Knights Armaments Company, M16A4s fitted with these handguards are formally known as the M16A4 Modular Weapons System. Colt and FN manufactured the M16A4 with both full auto and burst capabilities, although the US uses the variant with burst fire.

In the 2010's, both the US Marine Corps and the US Army conducted a unit-level upgrade to the M16A4, where adjustable stocks from the M4 were fitted. This was due to a more prevalent use of body armor by US forces during their more direct involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The fixed stocks proved cumbersome with body armor, especially with soldiers and marines of smaller build. While the Army and Marine Corps encourage their use and deployment, the fixed stocks must still be retained by the armorers.

Derivatives: Alternative Arrangements

The M16 assault rifle would form the basis for many designs, either by Colt, made under license, or unlicensed copies. These designs would in turn be the basis for further development. Due to the sheer number of derivatives, this will only cover the major derivatives in military use worldwide.

CAR-15, Commando, and the M4: Baby Armalite

As soon as Colt acquired the rights to the AR-15 design, they began development of several variants for military use, including shortened weapons. The resulting CAR-15 carbines were incredibly popular, and would evolve into the even more successful M4 Carbine. Further information can be found on my M4 Carbine build.

These shortened weapons found favor with police, military, and special operations customers. The M4 in particular had replaced the M16 as the primary service rifle of the US Armed Forces.

Colt 9mm SMG: The M16 goes 9mm

The Colt 9mm SMG is essentially the CAR-15 modified to use 9mm Parabellum. While the Colt 9mm SMG is externally quite similar and duplicates all the controls, the Colt 9mm SMG operates quite differently. Rather than Stoner's expanding gas system, the Colt 9mm SMG relies on direct blowback, where the momentum of the fired bullet is balanced by the mass of the bolt.

As a result of the use of direct blowback, the wear on trigger parts was increased, and were later strengthened. As part of the conversion, a magazine block was added in the magazine well to allow the proper fitting of 9mm magazines. The magazines themselves were modified Uzi magazines, with the addition of a bolt hold-open tab to allow the bolt hold-open mechanism to operate as intended.

The Colt 9mm SMG saw more limited success due to limited production and Colt’s marketing; they knew that the Colt 9mm was a direct competitor to compact carbines, including their own Colt Commando, and that it would be unwise to market products that cannibalize each other's sales. It was also anticipated that the Colt Commando would be a more attractive option for those looking for close-range firepower.

M231 Firing Port Weapon: Bradley’s Bullet Hose

The M231 Firing Port Weapon was a heavily modified M16 rifle designed specifically for the firing ports of what would become the M2 Bradley IFV. While the prototypes were fitted with flip-up sights and a wire collapsible stock akin to the M3 Grease Gun, the production weapons would have no sights or stock; the weapon was screwed into a firing port and aimed by “walking in” the tracers via vision blocks.

The internals of the FPW are very different; it fired from an open bolt, could only fire full auto, and had a completely new bolt carrier, buffer, buffer tube, trigger group, and recoil spring. Without any sights or stock, and a cyclic rate of 1100 rpm, it was mainly intended for suppressive fire.

The weapon is still in service, although armor upgrades to the M2 Bradley blocked off the side ports, leaving only two firing ports in the troop ramp. The weapon saw limited service in the 2003 Iraq War as means for Humvee and MRAP gunners to fend off enemy combatants too close to bring the turret-mounted weapons to bear.

Mk 12 SPR: 75 in 77

As early as 1965, sniper variants of the M16 were developed. However, it would not be until the late 1990’s did sniper variants of the M16 begin to enter service.

The Mk 12 SPR, or Special Purpose Rifle, was developed by NSWC Crane Division, who supports the maintenance and development for weapons intended for use by US Navy SEALS and also for weapons intended for other US Special Operations.

The Mk 12 SPR was designed as a way to provide a weapon in a weight, size, and performance capability between sniper rifles such as the SR-25, and the M4 Carbine. Improvements include a heavy match-grade Douglass 18” stainless steel barrel, an OPSINC quick-detach silencer, a free-floated fiberglass handguard and matching top rail extension manufactured by Precision Reflex Industries, or PRI, and a folding front sight with detachable folding rear sight, also made by PRI.

In addition, a variety of scopes were fitted, notably Leupold 2.5-8x36mm TS-30 scopes, as well as Nightforce 2.5-10x24mm NXS scopes. Night-vision optics can also be fitted.

To exploit the high precision of the Mk 12, the Mk 262 cartridge by Black Hills Ammunition was developed, using the heavier 77-grain (5.0 g) “Open-Tip Match” bullets made by Sierra Manufacturing, a company known for manufacturing bullets to a high degree of precision. The designation “Open-Tip Match” is necessary as part of the manufacturing of these bullets to leave an “open tip” which resembles a hollow-point bullet.

Both the rifle and ammunition have been tweaked over its service life, the most notable being the Mk 12 Mod 1 upgrade which replaced the PRI rail extension and free-float tube with a quad-rail free-float handguard developed by KAC.

The combination of the Mk 12 SPR with its highly effective silencer and accurization, high-quality optics, excellent Mk 262 ammunition, and highly-trained snipers is a deadly blend; in one mission a pair of unnamed US Special Operations snipers with the Mk 12 in Afghanistan scored 75 kills with 77 shots.

Diemaco C7 and C8: The Black Rifle of the Great White North

The Diemaco C7 and C8 are license-built derivatives of the Colt M16 and the CAR-15, respectively. Under the Small Arms Replacement Program in the 1980’s, they replaced the FN FAL and Sterling SMG. While they are mostly identical to the Colt weapons, they feature many changes.

The C7 rifle can trace its origins to the M16A1E1, the developmental predecessor to the M16A2, and would have features of both the M16A1 and M16A2. The barrel profile and handguards were identical to the M16A2, although the barrels were formed using Diemaco’s cold-hammer forging process, and a tapered front post was employed for finer target shooting.

The sights from the M16A1 were maintained, although a brass deflector was incorporated. The stock was made to M16A2 standards, although a shorter stock identical in length to the M16A1 stock but incorporating M16A2 improvements was also developed and issued. This is in line with the Canadian Army tradition of issuing rifles of different stock lengths to accommodate soldiers of different body builds.

The C8 Carbine can trace its origins to the earliest CAR-15s with 14.5” barrels, albeit with many of the features on the C7 and with a 1 in 7 twist barrel. It maintains the earlier “pencil” profile, and features a telescoping stock.

Both the C7 and C8 would see substantial development distinct from Colt models. The C7A1 would incorporate a 14-slot Weaver-type “Diemaco rail” to mount the Elcan C79 3.4x magnification optic, a development which pre-dates the M16A4. A detachable rear sight is also available, though rarely issued other than for CQB exercises. The C7A2 features further improvements, incorporating green handguards, a clamp-on rail section around the front sight gas blocks, and the green adjustable stock from the C8A3 carbine.

The C8 carbine’s development is far more varied as its development spans the transition from the CAR-15 to the M4, and follows a similar path. The C8A1 incorporates the same updates as the C7A1, while the C8A2 incorporates a heavier barrel but is otherwise unchanged from the C8A1. The C8 FTHB, or Flat-Top Heavy Barrel, employs an M4-style barrel in the same C8A1 package, and is a close analogue to the M4.

In the meantime, the British Special Air Service requested various changes, to include a longer and heavier 15.7” (399mm) barrel, a special “Simon Sleeve” and strengthened front sight gas block to enable the mounting of the AG36 grenade launcher, and KAC quad-rail handguards. The subsequent carbine developed would be known as the C8 Special Forces Weapon, adopted by the UK as the L119A1. The Canadian Army would adopt a modified version known as the C8A3.

A variant with a 10” (254mm) or 11.6” (295mm) barrel, known as the C8 CQB, is also available, as are the C7CT and the C8CT designated marksman rifles designed to score hits up to 600 meters. New upper receivers with integrated railed handguards, known as the IUR and the MRR, have been marketed as upgrades.

The C7 and C8 in all its forms have found significant favor with a variety of units outside of Canada, to include British special forces and Royal Marines, Norwegian special operations and police units, the Dutch and Danish Armed Forces, and Botswana.

Norinco CQ: Chinese Colt

The Norinco CQ is an unlicensed copy of the M16A1, manufactured by the China Ordnance Industries Group Corporation Limited, or Norinco. It is believed that they were reverse-engineered from M16A1 assault rifles acquired during the Vietnam War.

The CQ can be distinguished from the M16A1 in the use of round handguards of a different design to the Colt, unique shape to the stock, and a revolver-style pistol grip. In addition, the receiver is made from 6061-T6 aluminum alloy. While this alloy is weaker and less durable, it is cheaper and easier to work with, able to be injection-molded.

Several variants have been developed, to include a semi-automatic only variant for commercial sales on the civilian market, and a clone of the M4 carbine known as the CQ-A.

Introduced in 1980, the CQ is primarily intended for export, though some Chinese special counter-terror units use the CQ-A. As an export product, it has been successful, with known users including Cambodia, Iran, Sudan, Paraguay, and North Korea. It is known that the Defense Industries Organization of Iran manufactures an unlicensed copy of the CQ, known as the Sayyad, and that the Military Industry Corporation of Sudan manufactures a licensed copy of the CQ as the TERAB.

Technical Description

The M16 is a gas-operated, multi-lug rotating bolt, magazine-fed select-fire rifle. In the original AR-15 and the subsequent M16 guise, it is a true assault rifle. All variants have a cyclic rate between 750-900 rpm.

The M16 and M16A1 weighed 6.37lbs (2.89kg) unloaded and 7.5lbs (3.40kg) loaded with 30-round magazines, and was 39.00” (990.6mm) long. By the standards of the time, was a light and handy weapon, and its favorable characteristics still hold up to today’s shooters. With the M193 cartridge, it has an effective range out to 460 meters, well within the distances combat is expected to take place in.

The M16A2, A3, and A4 weigh 7.5lbs (3.40kg) unloaded, and a whopping 8.79lbs (4.0kg) with a sling and loaded 30-round magazine, and are 39.62” (1006mm). While somewhat heavier, the improvements gave it somewhat better shooting characteristics in exchange for weight and handling. The M855 cartridge and its heavier bullets allow it to engage targets at up to 550 meters, though the range dial indicates an optimistic 800 meter effective range.

Due to the popularity of the AR-15 system with militaries and gun enthusiasts, virtually every component is available from dozens of companies, and of varying quality.

Operating and Locking System

The M16 employs a unique “gas expanding system,” frequently and incorrectly referred to as a “direct impingement system.” This system vents gas into a chamber inside the bolt carrier group, which pushes the bolt carrier and the bolt apart, unlocking the bolt. Once the bolt is unlocked, the bolt carrier’s inertia sends the bolt back, where it is acted upon by the large recoil spring.

The force of the bolt carrier's movement is eventually overcome by the spring, which returns it forward at the end of travel, closing the action. In the process, the spent case has been ejected, and a new cartridge stripped from the magazine and loaded into the chamber.

Eugene Stoner's patent and Ian McCollum from Forgotten Weapons' video describing this system can best explain this.

Certain companies have adapted the AR-15 to use an external gas piston, including Colt. While these systems reduce fouling in the upper receiver and bolt carrier group, they are more complex and are harsher on the internal components, leading to increased parts breakage.

The AR-15, like the earlier AR-10, uses seven lugs arranged in a "star" pattern, with the extractor located where the eighth lug would have been. When firing, the rearward motion of the bolt carrier will rotate the bolt, unlocking it from the barrel extension.

One of the issues that plagued early M16s was the tendency for the bolt carrier group to "bounce," bumping slightly out of battery from the shock of the bolt carrier group slamming forward. While not an issue in semi-auto, it is an issue in full-auto, where the out of position bolt carrier group can absorb some of the energy of the hammer's fall, causing a misfire.

As a result, the early "Edgewood buffer", which was a hollow guide to prevent the recoil spring from binding up, was replaced by an aluminum "buffer" with five steel cylindrical free-moving weights, enclosed with a plastic cap at the back that doubles as a recoil buffer. The free-moving weights served as a dead-blow hammer to the bolt carrier group, neutralizing any potential "bounce" from the bolt carrier.

This buffer allowed the M16 to function with the new ammunition reliably. The CAR-15 and M4 employ a similar buffer, though it is much shorter and only contains three steel cylindrical free-moving weights. Some carbine buffers use tungsten weights to add mass and improve reliability.

Trigger Group/Safety

The M16 trigger group is largely unchanged between all the variants, with some exceptions.

It uses a single-action hammer, cocked by the moving bolt carrier group. When the trigger is pulled, the hammer is released, and falls onto the firing pin, which fires a round by detonating the cartridge's primer, igniting the propellant. The safety blocks the trigger from releasing the hammer. Most M16s have three position safeties, (safe-semi-burst/auto), though four-position safeties (safe-auto-semi-burst) also exist.

In semi-auto, when the bolt carrier group moves back, it forces the hammer into a trigger disconnector. The disconnector is important as it prevents the hammer from sliding on the bolt carrier as it returns to battery, which would cause a misfire. The hammer will stay in the disconnector until the trigger is released, where it will return to the cocked position.

In full-auto, the safety prevents the regular disconnector from moving, but allows the trigger to move freely. When the bolt carrier group forces the hammer back, the autosear will serve as the disconnector. When the bolt carrier group moves into battery, the "tail" of the bolt carrier group hits the auto sear, allowing the hammer to fall and fire the weapon. It will continue to fire until the trigger is released, the magazine has been emptied of ammunition, or in the case of a burst-fire weapon, when the disconnector is engaged.

For weapons with burst fire, a burst mechanism is incorporated into the fire control group, involving a notched cam, a spring clutch, and a modified trigger disconnector. For burst-fire, the cam is engaged when the trigger is pulled. While the weapon is firing, the shallow notches will engage the modified trigger disconnector twice, rotating the cam as it fires as if it was in full auto. On the third engagement, the notch is deeper, engaging the trigger disconnector as if in semi-auto, preventing the weapon from firing and requiring the trigger to be released. The cam rotates fully per every six shots, regardless of the safety's setting.

This system, intended to conserve ammo in automatic fire, is not without faults. Burst fire mechanisms add complexity and cost, reducing reliability. The M16's mechanism will always cycle when firing, even in semi-auto. In addition, the cam does not reset after every burst. As a result, it limits the burst to 1, 2, or 3 rounds. The burst mechanism also alters the trigger pull between shots, and the lack of a consistent trigger pull makes semi-auto fire less accurate on a practical basis.

This particular rifle has the option for safe, semi-auto, and full-auto.

Sights and Optics

The M16 rifle family uses a rear aperture and a squared front post with two large protective wings. This is a consistent feature not only with the M16 rifle family, but also with prior US service rifles such as the M1 Garand and the M14. Unlike prior rifles, the sight line is elevated due to the in-line stock.

The M16 and M16A1 utilize a two-position rear aperture with a short-range (300 meters and under) and a long range (~450 meters) setting, the latter marked with a large “L” under the sight. This rear sight is adjustable for windage, but requires a tool to do so, such as the tip of a cartridge.

The M16A2 utilizes a similar two-position rear aperture, albeit of different sizes. While the standard setting is identical to the A1’s aperture, the “L” setting is a large aperture of identical height, intended for use with the tritium-illuminated front post that was introduced in some M16A1 rifles and carried over to the M16A2. The aperture assemblies are interchangeable, so some M16A1s may have been fitted with this style of sight.

Where the M16 and M16A1 made the rear sight assembly part of the receiver itself, M16A2 put the assembly onto a separate part, whose elevation and range can be zeroed through the use of a pair of rotating dials underneath. Range adjustment is done by turning the lower dial, each click in 25-meter increments from 300-800 meters, or 300-600 meters on the M4. Elevation adjustment for zeroing the sights is done through the top dial, although an Allen key is required to allow the elevation to be adjusted. Windage is click-adjustable with a knob to the right, removing the need for a tool to adjust windage. This arrangement was considered more precise, but less durable than the M16A1 rear sight.

The M16, A1, A2, and A3 all employ some form of the distinctive “carry handle” as part of the upper receiver where the rear sight is mounted. The “carry handle” was a carryover from the AR-10 design, where it served to protect the top-mounted charging handle. Early AR-15 prototypes kept the top-mounted charging handle, but tended to get hot after many shots with either rifle. As a result, Jim Sullivan designed a revised T-shaped charging handle which was behind the rear sight, a design largely unchanged to this day.

The carry handle remained as removing it would require new and very expensive forgings. The fixture was then used to mount optics to the rifle, to include scopes, Weaver or Picatinny rail sections, night-vision sights, and a variety of reflecting sights. They can be fitted to the rifle by fitting the optic or rail into a channel cut into the top, and then screwing it from underneath. Modern detachable carry handle rear sights can also mount optics this way.

The M16A4 employs a “flat top” upper receiver which features a Picatinny rail on top. This allows the mounting of a variety of sights, to include a detachable carry handle rear sight, fixed or flip-up rear sights, red dot and holographic sights, scopes, and night vision/IR sights.

In all cases where it is present, the front sight is adjustable for elevation, and requires the use of a tool, such as a cartridge tip or nail. The only major difference between them is between the M16A4 and all prior models; the modified upper receiver raised the position of any rear sight mounted, requiring the front post to be mounted higher. These are marked with an “F” on the side, and are known as “F-marked” front sight gas blocks. The C7A1 also required the front sight to be raised for the same reasons, so they made the front sight post itself taller.

This rifle utilizes M16A1 sights and the M16A2 front sight block, identical to the Diemaco C7 rifle.

Magazines

The AR-15 feeds from double-stack, double-feed box magazines which lock the bolt open when empty. Original magazines were straight aluminum 25-round magazines based on the earlier AR-10’s. However, the slight taper of the .223 Remington cartridge meant that these magazines were unreliable, and the M16 would enter service with 20-round magazines. They were the primary magazine the rifle would utilize during the Vietnam War.

In Vietnam, encounters with the AK-47 and its 30-round magazine prompted the development of an equivalent for use with the M16. Aftermarket magazines are sometimes of higher capacity, to include quad-stack “casket” magazines or cylindrical “drum” magazines, of varying quality and reliability.

The M16 magazine’s aluminum construction was never a particularly durable solution, and the bend in the 30-round magazine’s body needed to accommodate the slightly tapered cartridges was a potential source of failures. The former issue prompted the development of magazines made of steel or plastic.

The latter issue prompted the development of “anti-tilt” magazine follower designs, as it is possible for the magazine’s follower plate to “tilt” inside the body, a condition found most often during automatic fire and causes failures to feed. A variety of designs made from plastic, distinguished by their color, were tested, starting from light green, tan, and gray/blue followers. The latest design is employed exclusively with a revised tan-painted magazine body, to allow improved reliability with the M855A1 cartridge. The variety of plastic magazines often utilize followers of their own design, with quality and function varying by manufacturer.

This rifle is fitted with a plastic 30-round magazine.

Stocks

The AR-10 and AR-15 uses an “in-line” stock configuration, where the stock is aligned with the barrel. This configuration ensures it recoils directly into the shooter’s shoulder, reducing muzzle rise and making rapid fire more accurate. A consequence of this configuration is that the sights needed to be placed higher up.

The M16 and M16A1 utilize a fixed stock made of phenolic resin soaked in cellulose. Inside the stock was a long buffer tube containing the buffer and the recoil spring. As cleaning kits were issued, a large stock compartment was added to store it.

The M16A2 would see improvements such as, making it from Zytel, lengthening the stock by 5/8” (16mm), and employing a plastic buttplate, although the compartment door was the same as the earlier rifles. This stock would be used on the M16A3 and M16A4.

The CAR-15 carbines use collapsible stocks as a way of reducing the weapons length. The M16 family requires the use of a buffer tube to contain the recoil spring and buffer, and thus cannot use a folding stock. As a result, a collapsible stock was developed for the CAR-15.

Originally with two positions (fully collapsed/extended), it was soon modified into an adjustable stock with 4-6 positions for use with shooters of different builds and with body armor. Some M16 variants would be equipped with them, notably the Diemaco C7A2.

This rifle uses a fixed M16A1-length stock.

Handguards

The original AR-15 handguards were a cylindrical design made from a paper-plastic blend, held with a round sheet metal handguard cap. These were fragile and difficult to replace as they required the removal of the muzzle device and front sight gas block.

This would be changed to a two-piece triangular design made from a phenolic resin blend. It is held in place with a four-piece slip ring applying spring pressure onto the handguard cap. This system would be used on virtually all M16 variants. Due to the triangular handguards, the M16 and M16A1 would use a triangular handguard cap.

In the late 1970’s, a new two-piece plastic handguard was developed, being a round design with identical top and bottom halves. This design simplified logistics, as the previous design had separate left and right halves. This development was independent of the M16A2, and the handguards could be used on all M16 rifles, and use the existing triangular handguard cap.

With the M16A4 came railed handguards. The aluminum handguards are heavier than the plastic models, but allow the mounting of various accessories such as bipods, foregrips, lights, and laser sights.

This rifle uses the round two-piece handguards with triangular handguard cap.

Accessories

The M16 originally came with a sling and the M7 Bayonet, with cleaning kits arriving later.

The sling is an olive drab two-point adjustable type made of nylon, which provisions for its attachment can be found with a fixed sling loop under the stock, and a swinging swing loop under the front sight block. While it is mainly to help carry the rifle on one’s shoulder in non-combat situations, it can also be used as a shooting aid.

In practice, a variety of slings, to include one- and three-point slings, are used with the M16, from various commercial manufacturers and of varying quality. In addition, they are frequently mounted where convenient, often tied and taped to the handguards, buttstock, on separate mounting points, or the front sight gas block. In some cases, the front sling swivel is removed or taped over.

The M7 Bayonet is a knife-type bayonet patterned off the M3 Fighting Knife, and in fact used the same M8 and M8A1 scabbard. The M7 Bayonet was later replaced by the M9 Bayonet, a functional copy of the Soviet AKM Type 2 bayonet. The US Marine Corps adopted the OKC-3S bayonet, which is closely patterned off the KA-BAR knife. Commercial alternatives, either clones of the above or new designs, exist, and are of varying quality.

The underside of the M16’s barrel would be able to host a variety of supporting weapons, requiring the partial removal or complete replacement of the handguards. These include grenade launchers such as the M203, or shotguns such as the KAC Masterkey.

Around the time of the Vietnam War, a sheet-metal bipod was developed for the M16A1, which could be clamped onto the barrel like an oversized clothespin. Intended to provide a more stable platform when firing prone in full auto, it was mainly issued to soldiers who were assigned the duties of automatic riflemen before the introduction of the M249 SAW.

While the ventilation holes of the handguard have been employed to mount a variety of other accessories on an ad hoc basis, the introduction of railed handguards enabled accessories such as laser sights, lights, and vertical foregrips to be fitted onto the rifle with relative ease.

A common accessory found on the M16 is a fabric storage pouch strapped to the stock, intended to hold a spare 30-round magazine or anything which can fit there.

Barrels

The M16 and M16A1 originally employed a narrow “pencil” barrel 20 inches (508mm) long, excluding the muzzle device. The use of a relatively thin barrel by today’s standards does not seem to be due to the smaller caliber as a similar exterior barrel profile was used on the earliest AR-10, but rather due to the AR-10’s origins as a military rifle, as military rifles traditionally had thinner barrels for weight reasons.

The main issue with the pencil barrel on the M16 was that the weapon heated up more rapidly than older weapons. Not only did this increase shot dispersion, but also caused unpredictable shifts to point of impact.

The US Marine Corps was unhappy with the pencil barrel for a variety of reasons and wanted a stronger, heavier barrel. That the US Marine Corps is especially proud of their tradition of marksmanship is well-known, and it is known that they would have liked a heavier barrel under the handguards.

The US Army objected because doing so would prevent the mounting of the M203 Grenade Launcher. The US Army was happy with the pencil profile, knowing that it was in fact quite strong already. As a result, a compromise was reached; the thickness of the barrel was unchanged under the handguards, but the front end was much thicker.

This created a more front-heavy weapon, which made it harder to shift point of aim but helped maintain said aim.

This rifle has an M16A2 barrel.

Muzzle Devices

The earliest AR-15 rifles lacked any muzzle device. However, the rifle soon gained a "duckbill" flash hider, consisting of three thin prongs, which were later strengthened. This would be a distinctive feature of early M16s and M16A1s. The "duckbill" flash hider was prone to damage and tended to get caught in gear or foliage.

As a result, the flash hider was changed to a cylindrical "birdcage" style flash hider, with six lengthwise, evenly-spaced ports across the circumference. This flash hider would be introduced on the M16 and M16A1, and rifles fitted with these would also be present in Vietnam, and in large numbers.

The M16A2 would alter the "birdcage" flash hider, with only five lengthwise ports, with a port on top, on each side, and between the top and side ports. The result of eliminating the bottom ports is that it deflected muzzle blast up, which reduced dust signature when firing prone and forced the muzzle down during rapid fire. As a result, they are technically compensators, although many call them flash hiders.

During the Vietnam War, the increase in covert activities meant a need for silencers, and naturally a few were acquired for the M16. The HEL M4 and the SIONICS MAW-A1 silencers would be successfully employed by various US special operations units, often as a "sniper" rifle as while the silencers did not completely eliminate the sound, it muffled it greatly, and its use made a well-camouflaged sniper virtually invisible.

The performance of the silenced M16s would pave the way for further use of silencers in the US Armed Forces, including the KAC M110 Semi-Automatic Sniper System which was also designed by Eugene Stoner, as well as in the Mk 12 SPR. However, when silencers became more utilized by US Special Operations and the 2015 US Marine Corps decision to fit all their weapons with silencers, it would be on the carbine derivatives of the M16.

This rifle uses an M16A2-style compensator.

Ballistic Performance

The ballistic performance of small-caliber high-velocity cartridges like the 5.56mm NATO utilized by the M16 has been controversial in the least.

There is little doubt to the excellent external ballistics of the 5.56mm round at distances of 300-500 meters, as the small, lightweight, but dense bullet flying over 900 m/s has a relatively flat trajectory, making it relatively forgiving to estimation errors in flight time and bullet drop. This is useful when trying to hit targets that are avoiding getting hit, such as varmint or combatants.

The terminal ballistics of the 5.56mm cartridge is hotly debated. The primary concerns which have been brought up are the issues of "stopping power", effective range, and increased availability of body armor able to stop 5.56mm ammunition. An argument is therefore made to move to larger, more powerful rounds.

The low "stopping power" is generally seen as lore backed by anecdotes than reality backed by science. The argument has thus moved to terminal effects at range, with specific emphasis on experience from the NATO intervention in Afghanistan, citing the use of Dragunov sniper rifles and PKM machine guns by insurgents. That said weapons were specifically designed to cover for the lesser range of the assault rifle, and that these weapons are designed to operate as part of a larger system, is conveniently ignored.

The ability to pierce body armor is a more valid concern. While standard 5.56mm NATO can pierce Kevlar vests even from the Colt Commando, new armor made of ceramic, steel, or even some plastics can stop even tungsten-core AP rounds. However, the high muzzle velocity of the 5.56mm has surprising capability against body armor, with standard steel-tipped M855 able to punch through armor that can stop lead-core 7.62mm ball ammo, and there is body armor which can even stop 7.62mm tungsten-core AP, a round able to pierce many light armored vehicles such as the Lenco Bearcat.

For the above reasons, the US Army is currently exploring a replacement for 5.56mm NATO as part of the NGSW program, the newest in a long line of M16 assassination attempts dating back from before the M16 was adopted, to employ an overcharged 6.8mm round with as much power as 7.62mm NATO, and every trick in the book to compensate for such power.

Commercial alternatives to 5.56mm NATO have been proposed, although the most successful tend to fill a niche. An example of this is the .300 Blackout cartridge, developed by AAC for use with silencers and very short barrels. It trades some velocity for mass, delivering more kinetic energy at any range at the cost of increased bullet drop, reducing effective range. It has found favor with select special operations units as well as hunters looking for more punch out of the AR-15.

Specifications

General Characteristics

- Predecessor M16 Replica

- Created On Windows

- Wingspan 6.6ft (2.0m)

- Length 97.4ft (29.7m)

- Height 25.2ft (7.7m)

- Empty Weight 1,057,046lbs (479,468kg)

- Loaded Weight 1,057,046lbs (479,468kg)

Performance

- Wing Loading N/A

- Wing Area 0.0ft2 (0.0m2)

- Drag Points 14283

Parts

- Number of Parts 1106

- Control Surfaces 0

- Performance Cost 2,641